The Virginia Festival of the Book — a vast selection of virtual, free panels and discussions with prominent writers — drew to a close on Friday. From children’s authors to University professors, this March has thus far been packed with phenomenal and accessible resources for readers and aspiring writers alike.

On Monday, in a discussion titled "The Art of the Short Story," Discussion Moderator Courtney Maum brought into conversation John Lanchester and Te-Ping Chen, authors of recently released and well-regarded short story collections. Fielding thought-provoking questions concerning their craft, the pair shared their experiences throughout the process of composing their recent collections, from initial inspiration to final revision.

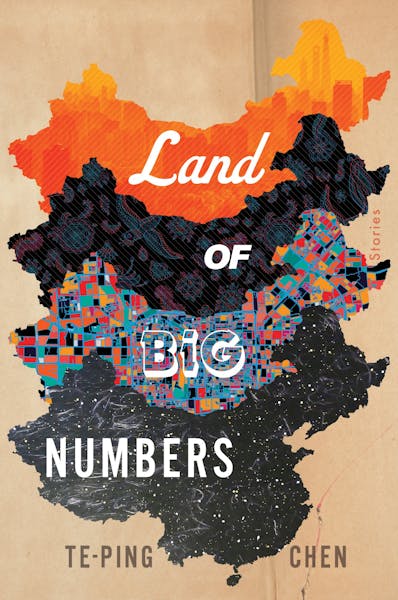

Maum began by inviting the writers to share the broader themes of their recently published collections. Chen — whose debut collection, "Land of Big Numbers," is a fictional glance into the Beijing she has reported on for the Wall Street Journal — has threaded absurdist humor and magical realism into a set of stories that reflect a spirit that struck her deeply during her time in China. Lanchester, with "Reality and Other Stories," has brought the modern terrors of technology against something akin to ghost stories, evoking “unheimlich” — the uncanny, or the sense of what Lanchester calls “like but not like.”

Rather than reading from their recent books, Maum asked the pair to read from what was not published, provoking a unique conversation focused on the less romantic end of the writing process. Chen shared an early opening to the story that became “Shanghai Murmur” — Lanchester, a story now altogether lost to publication.

Both authors found that often what initially excited them most in a story — perhaps having even inspired it — was what ended up feeling ever-so-slightly out of place. Whether a character in a novel or a full-fledged short story, sometimes it seems to have just “wandered in from a different book,” Lanchester said. The best, crudest and simplest writer’s advice on offer — ”slaughter your darlings.”

Priming the writers further, Maum read a snippet from an Amazon review of Lanchester’s collection that remarked, “reality is the most frightening place.” The collections of both writers resonate spectacularly well with a world haunted by COVID-19. The technology and “unheimlich” of Lanchester’s stories just as well as the inspiring yet terrifying adaptability found in Chen’s, though written in a different time, seem to presage our own. Lanchester likened the timing of publishing a book — often buffered by more than a year — to diving from a cliff when there seems no water below, blindly hoping the tides might rush in to catch your fall at the moment you land.

Chen, too, remarked on the seemingly prescient themes that dominate her stories — namely of growing comfortable in a repressive system and of confronting restraint or distortion that lies beyond individual control. What was written in the spirit of illuminating — in ways reporting cannot — the many colorful lives she crossed in China, Chen’s stories now resonate with the present moment more broadly. For Chen, journalism often brings to the reader only the resolution of some individual’s notable story — with fiction, she explains that readers can “unspool who they are [and] can start to see a whole world.”

Both writers return to the special light that the lens of fiction brings to bear on life. Lanchester, whose writings have dealt extensively with the sociological and political dimensions of technology, found that fiction can uniquely imagine the way current technology alters how we reason about the world and ourselves.

Technology and social media, to Lanchester, mold not only what lies external and observable, but perhaps also our very selfhood. Fiction, apart from other modes of writing, brings this most intimate aspect to light.

Before closing the event, Maum passed to Chen something between compliment and question concerning Chen’s potent metaphors of upward mobility that thread together her story collection. What Chen describes as “the upward gaze,” she found so strikingly animating in China and yet also so familiar back in the United States. The characters most dear to her heart were those so filled with wonder at possibility — a wonder magnified in China by the “scale of change and disruption that really lends itself to these extraordinary stories.”

Yet Chen also identified this wonder, this ability to see the world in its manifold possibilities, with empathy and with the desire to connect with others. Chen closed her remarks with a nod to the Virginia Festival of the Book, to the “fictional impulse” and all these forms of openness to possibilities and seeking after other worlds.

“It’s like the base of everything,” Chen said. “It’s our hunger for other people — it’s our understanding of other people.”

On this note, Maum brought the discussion to its conclusion, summarizing again the often haunting, ever-beautiful vistas each author paints. Both collections, above all, speak to “loneliness, and the impetus of all humans to avoid loneliness,” Maum said, and testify that perhaps fiction well remains one of our best avenues to “stay in conversation together.”

"short" - Google News

March 30, 2021 at 08:23AM

https://ift.tt/3sMzYlS

The art of the short story - University of Virginia The Cavalier Daily

"short" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2SLaFAJ

No comments:

Post a Comment